Responding to the Unthinkable: Legal Solutions in the Aftermath of a Disaster

COVID-19 isn’t the only calamity to hit Indiana. Floods, tornadoes, snowstorms and other disasters have happened since the beginning of Indiana’s settlement. The loss of business income, property and even lives in the aftermath of a disaster often generates disputes over questions of causation, prevention and loss control. Such disputes often expand into litigation.

Fortunately, Indiana has some of the best law in the country when it comes to insurance coverage for property losses and liability protection. Business owners need to familiarize themselves with their insurance policies or consult a coverage attorney to evaluate coverage options for losses arising from a communicable illness such as COVID-19.

But we live in Indiana. Aren’t we safe?

It is tempting to assume that disease epidemics occur only in Third World nations, or that hurricanes and terrorist attacks are problems for other parts of the country. COVID-19 demonstrates that Indiana is not immune. Not only do infectious diseases have the potential to affect the nation’s heartland: all kinds of natural calamities occur that threaten business operations here.

Flooding. Indiana is dissected by a large number of rivers and tributaries. Much of the state was formerly comprised of wetlands. Accordingly, much of the state is susceptible to severe flooding given the right circumstances. Excessive rain, rapid snowmelt, and frozen ground can combine to prevent the upper soil from allowing water to percolate downward, resulting in flooding.

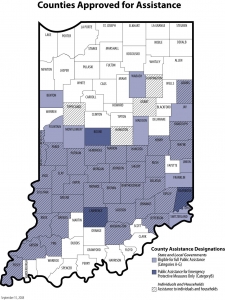

The June 2008 floods in Indiana are an example of the devastation that flooding can cause. That season, following an especially wet spring, nearly a foot of rain was dumped on saturated soils of Franklin and Edinburgh in seven hours. The rain was unable to infiltrate the waterlogged ground and was shed into the west and east forks of the White River, Flatrock River, and other smaller tributaries. The result for the surrounding areas of Franklin, Columbus, Martinsville and low lying parts of Brown County was record-setting high water levels and widespread damage. After the storms passed, all but 10 of Indiana’s 92 counties were declared disaster areas. At least two deaths resulted and an estimated half a billion dollars in damage was done in Columbus alone, where the hospital was inundated and closed for months.

Indiana received $67 million in federal emergency aid following damage caused by the June 2008 storms and flooding.

In addition to the risk of loss of life and damage to property associated with flooding, floods can cut off transportation routes and utility services. The loss of major transportation routes isolates entire communities and disrupts the distribution of food, medicine, goods and services. During the flood of 2008, several major highways in Indiana were closed including I-65, isolating communities until flood waters receded. In the infamous Flood of 1913, considered the most damaging disaster in Indiana history, the loss of life and property was unprecedented:

[T]housands were driven from their homes, fleeing for their lives; transportation lines were helpless through loss of track and bridges; telephone and telegraph lines were crippled; communities were cut off from communication with the outside world for from 24 to 48 hours; cities were deprived of light and power by the flooding of power plants; isolated towns were threatened with famine; and for a period of 3 days or more the great commercial enterprises of the State were at a standstill.[1]

Isolated, flooded communities often experience health problems, sewage system backups, and exposure to chemical releases caused by floodwaters invading industrial areas. Fire is another risk. Lack of accessibility makes combatting fires difficult and, as a result, portions of towns have burned to the ground during major floods.

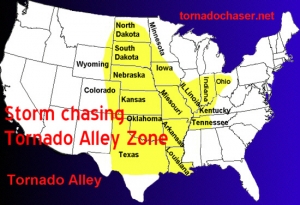

Tornadoes. In the 1970s, an average of 858 tornadoes occurred across the United States per year. In the 1990s, the national average increased by almost 30% to an average of a little over 1,200 tornadoes per year. Indiana experiences on average 22 tornadoes per year. Overall, most tornadoes (around 77%) in the United States are considered weak (EF-0 or EF-1) and about 95% of all United States tornadoes are below EF-3 intensity. The remaining small percentage of tornadoes are categorized as violent (EF-3 and above). Of these violent twisters, only a few (0.1% of all tornadoes) achieve EF-5 status, with estimated winds over 200 mph and nearly complete destruction. However, given that on average over 1,000 tornadoes hit the United States each year, that means that 20 can be expected to be violent and possibly one might be incredible (EF-5).

Each year or two brings violent tornadoes to Indiana but the worst by far was on Palm Sunday in April 1965. Never before had so many violent (F5 and F4) tornadoes been observed in a single tornado outbreak. There were seven F5 tornadoes and 23 F4 tornadoes. The disaster began in Illinois at around 1:00 pm on April 3. As the storm system moved east where daytime heating had made the air more unstable, the tornadoes grew more intense. A tornado that struck near Monticello, Indiana was an F4 and had a path length of 121 miles, the longest path length of any tornado for this outbreak. Seven F5s were observed—one each in Indiana, Ohio and Kentucky, three in Alabama and the final one which crossed through parts of Indiana, Ohio and Kentucky.

A total of 261 people were killed by tornadoes during the Palm Sunday onslaught, 138 of them from Indiana, 62 from Elkhart County. During the peak of the outbreak, sixteen tornadoes were on the ground simultaneously. At one point forecasters in Indiana, frustrated because they could not keep up with all of the simultaneous tornado activity, put the entire state of Indiana under a blanket tornado warning. This was the first and only time in U.S. history that an entire state was under a tornado warning.

Earthquakes. On December 15, 1811, an earthquake centered near the town of New Madrid in what is now southeastern Missouri sent shockwaves into the Indiana territory and beyond for hundreds of miles. The quake collapsed structures, toppled trees, and changed the course of the Mississippi River. During the next two months, the area would be rocked by three more quakes as powerful as the first and hundreds of smaller ones.

Since New Madrid, Indiana has felt many earthquakes, among them:

- 1895: the Charleston, Missouri quake damaged buildings in Evansville and other parts of southwestern Indiana.

- 1909: a quake originating near the Illinois border between Vincennes and Terre Haute knocked down chimneys, cracked building walls, severed light connections, and shook pictures off the walls.

- 1968: a magnitude 5.3 shock centered in southern Illinois was felt over 23 states including all of Indiana. In southwestern Indiana, chimneys were cracked, twisted, and toppled, groceries fell from shelves, and residents heard a loud roaring noise.

- 2004: a magnitude 3.6 earthquake centered near Shelbyville caused no injuries but caused minor damage to some structures.

- April 18, 2008: a 5.2-magnitude earthquake struck southeastern Illinois, 38 miles northwest from Evansville. The quake was felt throughout Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky.

- December 30, 2010: a magnitude 3.8 earthquake occurred near Greentown, Indiana, east of Kokomo. No injuries or damage was reported but residents in Indiana and surrounding states felt shaking.

- August 23, 2011: a 5.8-magnitude quake occurred in Virginia, 84 miles southwest of Washington, D.C. More than 240 Indiana citizens reported feeling the shock. Even earthquakes originating far away can be felt here and can happen anytime, without warning.

Living far from the West Coast is no immunity from earthquakes. A danger zone also exists at the New Madrid fault line with potentially damaging impacts in Indiana. Seismologists and geologists estimate a 90% chance of a magnitude 6–7 tremor before 2055, likely originating in the Wabash Valley seismic zone on the Illinois–Indiana border.

Blizzards and ice storms. In January 2014 we learned a new term: polar vortex. The polar vortex is a high altitude low-pressure system that hovers over the Arctic in winter. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the polar vortex acts like a spinning bowl balanced on the top of the North Pole. In January 2014, the polar vortex weakened and broke down, allowing frigid air to slosh out of the bowl into mid-latitudes, bringing heavy snow and near blizzard conditions to Indiana. Temperatures plummeted with wind chills around 40 below zero. The snow and cold shut down sections of interstate highways and paralyzed travel across the state.

NOAA explains: “In recent years, climate scientists have noticed that the jet stream has taken on a more wavy shape instead of the more typical oval around the North Pole, leading to outbreaks of colder weather down in the mid-latitudes and milder temperatures in the Arctic, a so-called ‘warm Arctic-cold continents’ pattern. Whether this is normal randomness or related to the significant climate changes occurring in the Arctic is not entirely clear, especially when considering individual events. But less sea ice and snow cover in the Arctic and relatively warmer Arctic air temperatures at the end of autumn suggest a more wavy jet stream pattern and more variability between the straight and wavy pattern.”

The Great Blizzard of 1978, also known as the White Hurricane, was a historic winter storm that struck Indiana and the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes from January 25 through January 27. The storm initially began as rain but quickly changed to heavy snow leading to frequent whiteouts and zero visibility during the day on January 26. As the storm headed for Ohio, it grew into a “storm of unprecedented magnitude,” according to the National Weather Service, which categorized it as a rare severe blizzard, the most severe grade of winter storm. Temperatures dropped to zero. Wind chills remained 40 to 50 below zero nearly all day. Snow drifts of 10 to 20 feet made travel virtually impossible, stranding an Amtrak train and thousands of vehicles and travelers. During the afternoon of January 26, the Indiana State Police declared all Indiana roads closed.

What are the legal considerations?

As business losses caused by COVID-19 begin to mount, clients should carefully review their insurance policies to determine whether they may be covered. For example, business interruption coverage, which is typically part of a commercial property insurance policy, covers economic losses resulting from a disruption in business operations. Business interruption insurance often is triggered only by physical loss or damage to covered property. At first glance, most insurers (and many agent/brokers) think this requires actual physical damage to the property. However, the law is unsettled on this. For example, damage is not the same as loss. Different courts around the country (including Indiana) have found a “direct physical loss” in the absence of actual physical damage. Some courts have even found that government orders requiring the loss of use of the facility constitute direct physical loss. The parallels to COVID-19 are obvious.

A business may also be covered for economic losses resulting from a disruption in the operations of a supplier or customer. As with business interruption insurance, this insurance often is triggered only by physical loss or damage to the supplier’s or customer’s covered property, but there may be exceptions.

Entertainment venues, theaters and other types of businesses may have coverage for the cancellation, postponement, or relocation of an event for reasons beyond the policyholder’s control. Also, virtually all businesses have coverage for general liabilities, which provide defense and indemnity coverage to help address facing lawsuits alleging, among other things, bodily injury.

With all of these types of coverage, the policy language is key, and it may vary in material ways. There are likely other issues well, such as exclusions and conditions that must be analyzed.

Legal basis for disaster planning. Schools, hospitals, offices, restaurants, high rise buildings, dams, bridges, data processing equipment and other structures and infrastructure are vulnerable in a disaster, whether caused by nature or by an explosion, jet airline crash, terrorist attack, nuclear power plant leak, pandemic, or chemical spill. The obligation to make reasonable plans to attempt to avoid or mitigate damage from a disaster stems from many sources:

- Environmental laws and regulations require companies managing hazardous materials to develop spill prevention and containment plans.

- Financial institutions, particularly those participating in the federal banking system, must comply with an array of regulations mitigating against computer failures and promoting data recovery.

- The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977, which was conceived as a mechanism to promote corporate transparency and punish the use of bribes for obtaining business advantage in foreign markets, imposes sweeping recordkeeping provisions that the Securities Exchange Commission has applied to all publicly held companies. These provisions require companies to safeguard records that clearly indicate how their assets are used. Under the law, a business must take measures to guarantee the security and integrity of its recordkeeping system – a provision that has been widely interpreted as a requirement to undertake contingency planning.

- Regulations from the Office of Management and Budget require government agencies to take adequate measures to safeguard the operations of their IT processing facilities. This rule has been interpreted to extend to government contractors and subcontractors.

In Indiana, the Security Breach Reporting Act, Ind. Code § 24-4.9-3, in effect since 2006, requires businesses to notify affected consumers and the Indiana Attorney General’s office following discovery of a security breach, which is defined as an unauthorized acquisition of computerized data which compromises the security, confidentiality or integrity of personal information. The statute seeks to alert Indiana residents when a security breach has resulted in the exposure of their personal information. “Personal information” means a Social Security number, or a person’s name and address plus any of the following: driver’s license number, state ID card number, credit or debit card number, or financial account number in combination with the security code or password that would permit access to the account.

Security breaches can be the result of a disaster. In 2006, high winds blew out windows at One Indiana Square, a 36-story office building in downtown Indianapolis, sending confidential documents sailing into the streets:

Or a breach can result from the simple theft of a laptop computer. If the breach involves the unauthorized acquisition of computerized data which compromises personal information, then pursuant to Ind. Code § 24-4.9-3-3 it must be reported without unreasonable delay by phone, mail or email. If the breach affects more than 1,000 Indiana residents, the notification must be made to consumer reporting agencies such as Equifax, Experian, and Transunion. The Attorney General may seek injunctive relief against any business for failing to comply, and a court may impose a civil penalty of not more than $150,000 per deceptive act, plus an award of costs to the Attorney General.

The common law duty of care. The general obligation of a landowner to protect against hidden dangers is well established: a property owner must maintain the property in reasonably safe condition for business invitees including independent contractors and their employees. Smith v. King, 902 N.E.2d 878, 881-82 (Ind. Ct. App. 2002). Further, the landowner owes a duty to warn of hazardous instrumentalities maintained by the landowner, or latent or concealed perils located on premises. Zawacki v. U.S.X., 750 N.E.2d 410, 414 (Ind. Ct. App. 2001).

Indiana follows the Restatement (Second) of Torts formulation of landowner’s premises liability. PSI Energy, Inc. v. Roberts, 829 N.E.2d 943, 957-58 (Ind. 2005). Under the Restatement, a possessor of land is subject to liability for physical harm caused to invitees by a condition on land if, but only if, the landowner (a) knows or by the exercise of reasonable care would discover the condition, and should realize that it involves an unreasonable risk of harm to such invitees (b) should expect that they will not discover or realize the danger, or will fail to protect themselves against it, and (c) fails to exercise reasonable care to protect them against the danger. Restatement of Torts, § 343. Further, Section 343A(1), which is meant to be read in conjunction with section 343, provides: “[A] possessor of land is not liable to his invitees for physical harm caused to them by any activity or condition on the land whose danger is known or obvious to them, unless the possessor should anticipate the harm despite such knowledge or obviousness.” While the comparative knowledge of landowner and invitee is not a factor in assessing whether the duty exists, it is properly taken into consideration in determining whether such a duty was breached. Rhodes v. Wright, 805 N.E.2d 382, 388 (Ind. 2004).

A landowner’s duty to protect against harm extends beyond immediate on-site users. For example, Indiana has long held that an owner whose construction interferes with the flow of a “natural watercourse” is liable to surrounding property owners for ensuing flood damage. Evansville, M. C. & N. R. Co. v. Scott, 114 N.E. 649 (1916). Thus, a Gibson County farmer whose land was submerged during the infamous Flood of 1913 was entitled to recover damages from the railroad companies whose tracks crossed her farm because the track bed, embankments and trestles interfered with the flow of the receding flood waters. The railroad pleaded, among other defenses, that the extraordinary flood was an “act of God.” But that defense was unavailing. Indiana recognizes force majeure as an excuse for failure to perform contractual obligations, when performance is prevented by circumstances beyond the parties’ control. But in torts, an act of God must be caused exclusively and directly by natural causes. When the cause is partly the result of human conduct, whether from active intervention or neglect, the whole occurrence is “humanized” and removed from acts of God.[2] Childs v. Rayburn, 346 N.E.2d 655 (Ind.App.1.Dist. 1976) (an act of God does not negate liability for concurring human negligence; where an act of God concurs with human negligence, negligence may result in liability for injury occurring as a consequence of combined forces); William H. Stern & Son, Inc. v. Rebeck, 277 N.E.2d 15 (Ind.App.1.Div. 1971) (for a defendant to be relieved from liability under an act of God defense, he must show that plaintiff’s injury was caused solely by an act of God). See also Nashville, C. & S. L. R. Co. v. Johnson, 60 Ind. App. 416, 419, 109 N.E. 912, 913 (1914); Pittsburgh, C. & S. L. R. W. Co. v. Hollowell, 65 Ind. 188, 194 (1879); Indianapolis & C. R. Co. v. Cox, 29 Ind. 360, 362 (1868).

The Evansville, M. C. & N. R. Co. v. Scott court not only rejected the “act of God” defense; it also rejected the defense that multiple factors, wholly unconnected to the defendants’ railroad tracks, had caused the flooding on plaintiff’s property. Defendants pointed out that flooding had started on distant upstream tributaries, giving rise to rapidly rising waters and generating drift and debris that floated downstream and clogged the passageway for waters underneath defendants’ railroad trestles. None of those concurring causal factors mattered:

It is not necessary, in order to hold one liable for negligence, that the particular consequence could by the exercise of ordinary care have been anticipated; the particular consequence need not in fact be anticipated. It is sufficient, if the probable injurious consequence that occurred could have been anticipated by the exercise of reasonable care, and not the number of intervening agencies that might arise in the bringing about of such consequences. In other words, it is sufficient if the injurious consequences were likely to occur by reason of the condition of the place and the surroundings.

114 N.E. at 656 (citations omitted).

Indiana Emergency Management and Disclosure Law. In Northern Indiana Public Service Co. v. Sharp, 790 N.E.2d 462 (Ind. 2003), a wrongful death case arising from flooding of the Little Calumet River near Highland in Lake County in 1990, the courts were forced to apply Ind. Code § 10-14-3,[3] which establishes the framework in Indiana for identifying, declaring and responding to state emergencies. In that case, a utility company, NIPSCO, was sued after helping the Town of Highland with emergency response assistance. The utility claimed immunity under the Emergency Management and Disclosure Law from any liability for negligence. The plaintiff was an employee of a trucking company under contract with Highland and tasked with hauling and dumping gravel as part of an emergency effort by Highland to construct a temporary berm to save the Wicker Park Manor neighborhood from being further inundated by flood waters. Part of the berm passed underneath the NIPSCO overhead power lines. As the plaintiff raised his truck bed to dump gravel, the truck became energized by proximity to NIPSCO’s overhead powerlines. The driver leaped from his truck, landed in water, and died from electrocution.

Under the Emergency Management and Disaster Law, the state and political subdivisions and anyone qualifying as an “emergency management worker” are entitled to broad tort immunity. The statute provides:

Any function under this chapter and any other activity relating to emergency management is a governmental function. The state, any political subdivision, any other agencies of the state or political subdivision of the state, or, except in cases of willful misconduct, gross negligence, or bad faith, any emergency management worker complying with or reasonably attempting to comply with this chapter or any order or rule adopted under this chapter, or under any ordinance relating to blackout or other precautionary measures enacted by any political subdivision of the state, is not liable for the death of or injury to persons or for damage to property as a result of any such activity.

NIPSCO was an “emergency management worker” under the statutory definition of that term, which included “any agency or organization” engaged in “performing emergency management services at any place in Indiana subject to the order or control of, or under a request of, the state government or any political subdivision of the state.” Ind. Code Ann. § 10-14-3-3. Therefore, NIPSCO was immune from liability for negligence.

The decedent’s estate argued that the statute by its terms provided immunity only for simple negligence. Here, the estate alleged that NIPSCO had been grossly negligent. Thus, there was no immunity under § 10-14-3-15.

The Porter County Superior Court initially granted summary judgment on all claims in NIPSCO’s favor. The Court of Appeals reversed, holding that while NIPSCO was immune from liability for simple negligence, a trial was needed to determine if NIPSCO had been guilty of gross negligence or worse. The case then went to trial and the jury found for the estate. The court awarded $750,000 in damages. However, in a second appeal the Court of Appeals reversed again, this time holding that the trial court should have granted NIPSCO’s motion for judgment on the evidence. NIPSCO v. Sharp, 732 N.E.2d 848 (Ind. Ct. App. 2000).

The decision by Judges Bailey, Baker and Mattingly is interesting, although short-lived as it was ultimately reversed by the Indiana Supreme Court. The Court of Appeals discussed the problem of identifying duties of care, determining their extent, and reconciling this with the public policy imperative, as reflected in the Emergency Management and Disaster Law, of facilitating rescue and remedial measures in a disaster.

The Court of Appeals held that although NIPSCO owed a duty of reasonable care to keep distribution and transmission lines safely insulated in places where the general public may come into contact with them, it owed no duty of care specifically to the decedent:

Here, where the Town of Highland was a disaster area and town officials restricted access to the flood area to emergency workers only, it was the Town of Highland, not NIPSCO, which ensured that the general public did not come into contact with the at-issue power lines. Moreover, it may be generally said that the Town of Highland “was in control of the [flood] situation.” Therefore, while NIPSCO had a relationship with, and a duty to exercise reasonable care for, the general public of Highland, it is not reasonable to extend this relationship, and its corresponding duty, to Krooswyk Trucking and its employees.

732 N.E.2d at 857. If any duty of care owed was owed to the decedent, it was owed by the Town Highland, the entity in control of and dealing with the flood emergency. Highland, however, as a political subdivision of the state, was immune from tort liability under the Emergency Management and Disaster Law.

The Court of Appeals also considered whether evidence at trial might have allowed the jury to infer that NIPSCO had actual knowledge of an electrocution risk posed to the decedent, or that NIPSCO was generally aware of the risks associated with flood conditions. That would be relevant to whether the law should impose a duty of care running to the decedent. In Indiana, whether to recognize a duty of care is based on a balancing of three factors: (1) the relationship between the parties; (2) the reasonable foreseeability of harm to the person injured; and (3) public policy concerns. Webb v. Jarvis, 575 N.E.2d 992, 995 (Ind. 1991).

The Court of Appeals held that there was no evidence that NIPSCO knew anything about a gravel berm being constructed underneath its high power wires. The court noted that the decedent had been allowed to introduce expert witness testimony that NIPSCO should have done a better job preparing for a flood emergency. Among other things, NIPSCO should have posted signs and barricades to keep people from getting too close to the high power wires. But that didn’t matter, according to the court, as NIPSCO had no idea that anyone was constructing a gravel berm anywhere near its wires.

The court also found that as a matter of public policy, no duty of care between NIPSCO and the decedent should be recognized as that would interfere with the purpose of the Emergency Management and Disaster law to promote an efficient response to emergencies by broadly immunizing emergency responders from tort liability.

The Indiana Supreme Court granted transfer and reversed. Northern Indiana Public Service v. Sharp, 790 N.E.2d 462 (Ind. 2003). It held that NIPSCO did in fact owe a clear, well recognized duty of care “to keep distribution and transmission lines safely insulated in places where the general public may come into contact with them.” That duty ran in favor of the decedent, not just the public at large. Accordingly, there was no need for the Court of Appeals to engage in a lengthy analysis under Webb v. Jarvis as to the existence of a duty of care: “we already know,” 790 N.E.2d at 465, because the duty has been previously declared in prior cases. Also, the Supreme Court held that the Court of Appeals erred in reversing the trial court over a denial of a motion for judgment on the evidence. Such a motion should be granted where there is only one conclusion the jury could have found — i.e., no gross negligence. Here, the evidence was disputed and reasonable people could come to differing conclusions. Thus, the motion for judgment on the evidence had been correctly denied.

Tort liability for injury in a disaster. Cases from around the country recognize the potential liability of property owners for failing to adequately anticipate and prepare for a calamity. Typical is HRD Corp. v. Lux International Corp., 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 51688 (S.D. Tex. 2007), one of many cases arising from Hurricane Katrina in 2007. Lux International ran a wax processing facility in Mississippi, east of New Orleans, less than two miles from the Gulf Coast. Plaintiff was a chemical company that had shipped unprocessed wax by rail to Lux. In the months prior to Hurricane Katrina, HRD had shipped two rails cars of unprocessed wax to Lux. The rail cars were sitting on a railroad siding on August 29, 2007, the day the hurricane hit. Meanwhile, Lux had processed other wax belonging to HRD, and that product was stored in bags inside the Lux warehouse. The hurricane knocked the railcars off the track and flooded the Lux buildings. All the wax, processed and unprocessed, plus the two railcars, were destroyed.

HRD sued for negligence and bailment, claims that easily could have been brought in Indiana had the disaster occurred here. HRD acknowledged that Hurricane Katrina was a massive act of God, but argued that Lux could have done more to have mitigated the loss. Specifically, Lux could have shipped the HRD wax further inland to escape the hurricane. But the evidence from Lux showed that Lux had monitored weather reports and no one knew until August 27, two days before the hurricane hit, that the eye of the hurricane would pass overhead. By then it was too late for anyone to arrange for a rail shipment of wax. Lux personnel moved property inside buildings and did their best to lock down the buildings in preparation for the onslaught. The Lux plant manager testified: “All the property on the premises, both that belonging to Lux and its customers was protected to the best of the Lux crew’s ability, under the circumstances. In general, I took the same sorts of precautions at the plant as I did for my own property. I know of nothing I could have done, under the circumstances, to avoid the damage that occurred.” 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 51688, *7-8.

Another seemingly key piece of evidence was that HRD itself had not taken measures to retrieve its property prior to the storm. The court held there was no reason to withhold judgment for Lux:

The record shows that Lux took reasonable steps to protect the equipment, structures, and inventory at its Pass Christian plant, but was limited in what it could do to move inventory or equipment to a safe place because the path of the storm became clear only two days before it hit. The record also shows that the effectiveness of what Lux did was limited by the unprecedented force of the storm and height of the resulting surge. Given the uncontroverted evidence as to

what Lux and HRD did to prepare, there is no basis to find a disputed fact issue as to whether Lux’s preparations were negligent or whether those steps contributed to the damage resulting from the hurricane.

2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 51688, *34.

Thus, the fact that the landowner paid close attention to weather reports and reacted as best it could under the circumstances helped save it from liability. In the next case, the landowner’s close attention to weather reports had precisely the opposite result:

In Mostert v. CBL & Assocs., 741 P.2d 1090, 1091 (Wyo. 1987), a family went to see the movie European Vacation at a theater in Cheyenne, Wyoming. They left the theater after the show ended. During the movie, the National Weather Service and local authorities broadcast warnings about severe thunderstorms and tornadoes and warned citizens to stay indoors. Movie theater personnel were aware of the warnings, but did nothing to advise guests inside watching the show. On the way home, the family ran into a flash flood. The family’s 7-year-old daughter drowned as the family attempted to escape their vehicle.

The girl’s estate sued the shopping mall that owned the theater building as well as the movie theater business. The trial court granted the movie theater’s motion to dismiss and the shopping mall’s motion for summary judgment.

On appeal, the court reversed the portion of the order that dismissed the claim against the theater. The court held that the deceased was a business visitor-invitee to the theater. The court held that the theater had knowledge that flooding was occurring outside the mall and that a flash flood warning was issued by the city. The court balanced a multi-factor test in concluding that the weather risks to the decedent outweighed whatever minimal burden would be placed on theater personnel to reveal their knowledge about the severe weather:

[W]e do not detect a public policy against imposing a duty on AMC to advise patrons of off-premises dangers. The risks to which the Mostert family were exposed far outweighed the minimal burden placed on AMC to reveal its knowledge to its patrons.

741 P.2d at 1096. However, the court affirmed the portion of the order granting summary judgment for the shopping mall owner. The court held that the landlord was not in possession of the theater and could not have warned patrons about any weather dangers.

Indiana State Fairgrounds disaster. In 2016, the Indiana Supreme Court ruled that the state is not liable to pay damages incurred by a company that provided stage rigging that collapsed and killed seven people during the 2011 state fair. Mid-Am. Sound Corp. v. Ind. State Fair Comm’n (In re Ind. State Fair Litig.), No. 49S02-1601-CT-51, 2016 Ind. LEXIS 65 (Jan. 28, 2016). Mid-America Sound Corp. had argued that a voucher claim form the State Fair Commission signed months after the collapse included an “indemnification” provision that released it from any claims arising from the use of its equipment. The contract provided:

[The Commission] assumes risks inherent in the operation and use of the equipment and agrees to assume the entire responsibility for the defense of, and to pay, indemnify and hold [Mid-America] harmless from and hereby releases [Mid-America] from any and all claims for damage to property or bodily injury (including loss of life) resulting from the use, operation or possession of the equipment, whether or not it be claimed or held that such damage or injury resulted in whole or in part from [Mid-America’s] negligence, from the condition of the equipment or from any cause, [the Commission] agrees that no warranties, expressed or implied have been made in connection with this rental.

The Indiana Court of Appeals had ruled a year earlier, in a 2-1 decision, that the indemnity provision was not mere “boilerplate” verbiage (“something inserted on the back of an invoice,” according to the Attorney General’s office), but was, in fact, an important part of a binding contractual agreement. The Supreme Court, however, ruled unanimously that the voucher form’s language “did not clearly and unequivocally provide for retroactive application” of that provision for any claims arising from the deadly rigging collapse. Mid-America argued that although the contract had been signed after the tragedy, the parties’ course of dealing over many years – in which the Commission executed equipment lease documents only after the fair had concluded and Mid-America had retrieved its equipment — established that the indemnity language was not being applied retroactively. The Supreme Court disagreed:

Indiana law likewise requires a “clear and unequivocal” expression of a “knowing[] and willing[]” agreement to indemnify a party for its own negligence—and moreover, to say so “explicitly” if they further intend that liability “to cover existing losses.” Even accepting all of Mid-America’s evidence as true for purposes of summary judgment, the parties’ course of dealing cannot substitute for a “clear and unequivocal” indication in the contract itself that the Commission “knowingly and willingly” agreed to indemnify Mid-America for its own negligence in connection with a catastrophic loss that had already happened.

2016 Ind. LEXIS 65, at *18 (Jan. 28, 2016) (citations omitted).

Indiana has already paid the statutory maximum liability, $5 million, to victims and surviving family members affected by the 2011 collapse. An additional $6 million, approved by the General Assembly, has since been paid as well, bringing the state’s payments to victims to a total of $11 million so far.

Another type of disaster: violence in the workplace. Shootings at work and other instances of workplace violence are increasingly common around the country, although fortunately not yet in Indiana. When workplace violence occurs, what is the employer’s liability?

Indiana cases generally hold that “proprietors owe a duty to their business invitees to use reasonable care to protect them from injury caused by other patrons and guests on their premises, including providing adequate staff to police and control disorderly conduct.” Muex v. Hindel Bowling Lanes, Inc., 596 N.E.2d 263, 266 (Ind. Ct. App. 1992). However, there is no duty on the part of a business owner to protect its patrons from the criminal acts of third persons unless the particular facts make it reasonably foreseeable that the criminal act will occur. Fast Eddie’s v Hall, 688 N.E.2d 1270, 1272-73 (Ind. Ct. App. 1997).

Simply because an injury has been inflicted at a person’s workplace does not mean that the injury is work related. It might be purely personal. For example, in Luong v. Chung King Express, 781 N.E.2d 1181 (Ind. Ct. App. 2003), a case involving a restaurant proprietor who was shot and killed as he stopped to pick up his workers to drive them to work, the court held that the shooting was completely non-work related: the shooter was not an employee and the reason for the killing was unconnected to the decedent’s employment. “An injury, by an employee, sustained in the course of his employment in a fight with a co-employee which does not arise out of the employment is not compensable under the [Worker’s Compensation] Act.” Id. See also Peavler v. Mitchell & Scott Mach. Co., 638 N.E.2d 879, 881 (Ind. Ct. App. 1994) (“When the animosity or dispute that culminates in an assault on the employee is imported into the workplace from the claimant’s domestic or private life, and is not exacerbated by the employment, the assault cannot be said to arise out of the employment under any circumstances.”).

Moreover, if the infliction of the injury was not purely personal but had a connection to the victim’s employment, then it is not clear the victim has any available tort remedy but may be consigned to his or her remedy under the Indiana Workers Compensation Act, Ind. Code § 22-3-2. Section 6 of the statute provides:

The rights and remedies granted to an employee subject to the Worker’s Compensation Act on account of personal injury or death by accident shall exclude all other rights and remedies of such employee, the employee’s personal representatives, dependents, or next of kin, at common law or otherwise, on account of such injury or death.

The exclusivity provision of the Act limits an employee to the rights and remedies provided by the Act where an employee’s injury meets the jurisdictional requirements of the Act. For an injury to be compensable under the Act, it must both arise “out of” and “in the course of” the employment. Greenberg News Network v. Frederick, 793 N.E.2d 311, 316 (Ind. Ct. App. 2003). The phrase “arising out of” refers to the origin and cause of the injury; the phrase “in the course of” refers to the time, place and circumstances under which the injury occurred. Nelson v. Denkins, 598 N.E.2d 558, 561 (Ind. Ct. App. 1992), quoting Skinner v. Martin, 455 N.E.2d 1168, 1170 (Ind. Ct. App. 1983). Thus, for an injury to arise out of and in the course of employment, it must occur within the period of employment, at a place or area where the employee may reasonably be, and while the employee is engaged in an activity at least incidental to his employment. Price v. R & A Sales, 773 N.E.2d 873, 875 (Ind. Ct. App. 2002), trans. denied.

Ordinarily an assault by a third person not connected to the employment cannot be considered incidental to the employment. A personal squabble with a third person culminating in an assault is not compensable. However, where the assault is one which might be reasonably anticipated because of the general character of the work, or the particular duties imposed upon the workman, such as a baking route salesman who carried money and was shot and robbed, or a night watchman killed by intruders, such injuries and death may be found to arise out of the employment.

Wayne Adams Buick, Inc. v. Ference, 421 N.E.2d 733, 736-37 (Ind. Ct. App. 1981) (citations omitted).

The cases do not always produce consistent results. Compare:

- Eagledale Enterprises, LLC v. Cox, 816 N.E.2d 917 (Ind. Ct. App. 2004) (bartender involved in brawl at work soon after going off her shift — held: tort claim not precluded by WCA, notwithstanding that employee had interceded in fight to protect customers);

- Wayne Adams Buick v. Ference, supra (bookkeeper was mugged as she deposited employer’s mail in the mailbox at the end of her shift—held: claim fell within the WCA);

- Peavler v. Mitchell & Scott Mach. Co., 638 N.E.2d 879 (Ind. Ct. App. 1994) (woman shot and killed at work by her boyfriend – trial court held for the employer that the claim was precluded by the WCA, but Court of Appeals reversed, finding the murder had nothing to do with the employee’s work).

Demarcating when an employee is “at work” is a fact intensive inquiry. “[A] servant’s employment is not limited ‘to the exact moment when the workman reaches the place where he is to begin his work, or to the moment when he ceases that work. It necessarily includes a reasonable amount of time and space before and after ceasing actual employment, having in mind all the circumstances connected with the accident.” 421 N.E.2d at 736.

In conclusion, an employer’s tort liability for injuries inflicted on employees will depend in significant measure on whether the violence can be seen as having arisen out of the employment – specifically, whether the character of the victim’s work or the particular job duties imposed on the employee exacerbated the risk that the employee would be attacked. If so, the episode may have arisen “out of” and “in the course of” the employment and will be subject to the exclusive remedy of the workers compensation statute. There will be no tort exposure.

……

Disasters, natural and otherwise, are increasingly unavoidable aspects of modern life. To minimize disaster-related litigation risk, clients must be able to convincingly demonstrate that they confronted and responsibly prepared to mitigate disasters. Lawyers can help clients begin that process by straightforwardly explaining that disasters do occur in the nation’s heartland – even in Indiana.

[1] Indiana Underwater: the Flood of 1913, http://www.in.gov/dnr/historic/files/hp-1913_flood.pdf.

[2] The principle has thus been succinctly stated: “He whose negligence joins with the act of God in producing injury is liable therefor.” 1 Am. Jur. 2d, Act of God, § 11.

[3] The statute was codified and written slightly differently at the time of the NIPSCO v. Sharp case and was known then as the Civil Defense and Disaster Law. Here we will cite to the current version of the statute, now known as the Emergency Management and Disaster Law, Ind. Code 10-14-3.